My research integrates Inuit traditional knowledge and genetic techniques to develop novel techniques in monitoring polar bears. This work includes documenting Inuit methods of identifying polar bear population characteristics such as sex, age, body size, and health of individual bears. This work also involves genetic methods of measuring telomeres—protective sequences at the ends of DNA that shorten with cell division—as an indicator of ageing in polar bear tissues collected by Inuit hunters during harvests. In this manner, partnerships with Inuit communities are critical for my research.

My research integrates Inuit traditional knowledge and genetic techniques to develop novel techniques in monitoring polar bears. This work includes documenting Inuit methods of identifying polar bear population characteristics such as sex, age, body size, and health of individual bears. This work also involves genetic methods of measuring telomeres—protective sequences at the ends of DNA that shorten with cell division—as an indicator of ageing in polar bear tissues collected by Inuit hunters during harvests. In this manner, partnerships with Inuit communities are critical for my research.

Last spring, in March and April 2014, I visited Arctic Bay, Arviat, and Kimmirut communities to initiate interviews with elders and hunters. This meant 56 cups of tea and over 300 hours shared over stories about hunting experiences, methods of identifying and distinguishing polar bears, and perspectives on research and monitoring programs. This February, I re-visited each community to re-cap my findings and seek insight for new directions in my work. I learned that despite my research plan, there are unanticipated themes and priorities that emerge upon arrival in each community and that the wisdom and expertise elders can share with me—within and outside of the context of my research—offer unique ways to acquire knowledge and interact with the world.

Last spring, in March and April 2014, I visited Arctic Bay, Arviat, and Kimmirut communities to initiate interviews with elders and hunters. This meant 56 cups of tea and over 300 hours shared over stories about hunting experiences, methods of identifying and distinguishing polar bears, and perspectives on research and monitoring programs. This February, I re-visited each community to re-cap my findings and seek insight for new directions in my work. I learned that despite my research plan, there are unanticipated themes and priorities that emerge upon arrival in each community and that the wisdom and expertise elders can share with me—within and outside of the context of my research—offer unique ways to acquire knowledge and interact with the world.

For one, community members stressed the importance of learning by experience. It was important to spend time on the land to understand the information and knowledge that the elders share. I have camped out on the land in M’Clintock Channel in the past which tends to be quite flat and, during foggy weather conditions bears a striking resemblance to the scene from the Matrix where Morpheus introduces Neo to the Matrix in the “loading stockroom”—a room of infinite emptiness against a backdrop of perpetual white with an indistinguishable horizon. Appropriately, these weather conditions are called “white outs”. However (and to return from my nerdy detour), Baffin Island is blessed with a sprinkle of mountains, which paints an entirely different picture. This became clear to me when local community members took me out in their trucks to point out key hunting areas and stories about the land that differed across communities:

Arctic Bay “Ikiaparjuk” means “pocket’, because it is situated in an inlet. A local hunter showed me areas to find seal and, as one might expect, hunt side by side with polar bears.

Arctic Bay “Ikiaparjuk” means “pocket’, because it is situated in an inlet. A local hunter showed me areas to find seal and, as one might expect, hunt side by side with polar bears.

Kimmirut, on the other hand, means “heel”, because it is situated across from a rock that resembles the bottom of one’s foot. Here, hunters are less interested in hunting polar bears but still participate in sample collection when the opportunity presents itself.

Arviat was named after bowhead whale, and was formerly referred to as Eskimo Point. This community experiences polar bears on a daily basis in the fall and avoiding potentially aggressive bears is an ongoing priority in the community. Unfortunately, my time in Arviat was dominated by a blizzard—40 to 60km/hr winds, zero visibility, and down to -56C temperature at times—which kept me in the north 5 days longer than I had originally planned for. On the positive side, this allowed more time to chat with community members about their polar bear experiences and gain some insight into new research directions. I also got to participate in a traditional feast run by a local group of women, and got a tour and brief history of the town with a local Inuit RCMP officer. This experience allowed me to practice adaptability in challenging, unpredictable environments. I am full of gratitude for what initially seemed like a “negative” turn in events.

Some would argue that rapidly growing social media is not necessarily the best for our culture but with growing access to Facebook in the north, I am grateful for being able to keep in touch and in contact with my northern friends. I continue to learn and develop new research ideas through our interactions until my next visit. Stay tuned for more updates!

Some would argue that rapidly growing social media is not necessarily the best for our culture but with growing access to Facebook in the north, I am grateful for being able to keep in touch and in contact with my northern friends. I continue to learn and develop new research ideas through our interactions until my next visit. Stay tuned for more updates!

APECS and the manufacturer of extreme-weather outerwear,

APECS and the manufacturer of extreme-weather outerwear,  My next adventure takes me to the Columbia Icefield – situated in the Canadian Rockies. The Columbia Icefield is a 'hydrographic apex', which means it is the meeting point of three continent wide watersheds. Its six major glaciers release melt water to three different oceans - reaching the Arctic, Pacific, and the Atlantic Oceans, and it significantly contributes to the fresh water supply of Canada and North America. Most glaciers here are remote and not easily accessible except by helicopter, but some are close to roads or established hiking trails. Notable among these are Athabasca and Saskatchewan glaciers in the Alberta Rocky Mountains.

My next adventure takes me to the Columbia Icefield – situated in the Canadian Rockies. The Columbia Icefield is a 'hydrographic apex', which means it is the meeting point of three continent wide watersheds. Its six major glaciers release melt water to three different oceans - reaching the Arctic, Pacific, and the Atlantic Oceans, and it significantly contributes to the fresh water supply of Canada and North America. Most glaciers here are remote and not easily accessible except by helicopter, but some are close to roads or established hiking trails. Notable among these are Athabasca and Saskatchewan glaciers in the Alberta Rocky Mountains. The subglacial environment is the small area that exists between the base of the glacial ice and the bedrock it rests on. In this small area melt water and ice interact with, and break down (i.e. physically and chemically weather) the bedrock releasing and transporting elements, nutrients and sediments out of the subglacial environment into downstream environments. Glacially fed streams have unique biological, chemical, and physical traits, which are carried out and passed on to downstream aquatic systems, including the ocean. These processes can have a significant impact on global biological and chemical cycles; understanding how glacier runoff interacts with downstream environments is critical for predicting the ecological effects of glacier change from the Columbia Icefield. Investigation of subglacial hydrology forms an important branch of glaciology as (a) this water exerts a strong influence on the motion and speed of ice masses through ice-water-rock interactions; (b) represents both a resource and hazard due to the release of chemicals on short and long term time scales, delivering nutrients and contaminants to terrestrial and aquatic environments, and (c) water may be stored for long periods in isolated subglacial lakes, allowing distinctive microbiological forms to evolve which are then released downstream; despite the wealth of information about chemical records in snow and ice, little information exists on the microorganisms.

The subglacial environment is the small area that exists between the base of the glacial ice and the bedrock it rests on. In this small area melt water and ice interact with, and break down (i.e. physically and chemically weather) the bedrock releasing and transporting elements, nutrients and sediments out of the subglacial environment into downstream environments. Glacially fed streams have unique biological, chemical, and physical traits, which are carried out and passed on to downstream aquatic systems, including the ocean. These processes can have a significant impact on global biological and chemical cycles; understanding how glacier runoff interacts with downstream environments is critical for predicting the ecological effects of glacier change from the Columbia Icefield. Investigation of subglacial hydrology forms an important branch of glaciology as (a) this water exerts a strong influence on the motion and speed of ice masses through ice-water-rock interactions; (b) represents both a resource and hazard due to the release of chemicals on short and long term time scales, delivering nutrients and contaminants to terrestrial and aquatic environments, and (c) water may be stored for long periods in isolated subglacial lakes, allowing distinctive microbiological forms to evolve which are then released downstream; despite the wealth of information about chemical records in snow and ice, little information exists on the microorganisms. As temperatures drop from summer into autumn and winter the amount of melt water generated at the surface of the glacier decreases and with the onset of freezing, the surface (supra glacial), inner glacier (englacial) and sub (base) channels which carry melt water through the glacier to the toe begin to freeze and contract. The effect of the hydrologic network closing at the end of the melt season is an aspect of glacial hydrology and chemistry that is currently insufficiently addressed. The timing of water delivery from glaciers is uncertain as climate change will fundamentally alter glacial recession rates and melting. For example, glacier recession in western Canada has led to changes in melt water pulses in the late summer with negative consequences for populated downstream environments, such as the arid Canadian Prairies, that are now subject to an impending water crisis. In particular, the Athabasca Glacier retreated only about 200 m between 1844 and 1906 but receded over 1 km during the next 75 years and lost nearly half its volume.

As temperatures drop from summer into autumn and winter the amount of melt water generated at the surface of the glacier decreases and with the onset of freezing, the surface (supra glacial), inner glacier (englacial) and sub (base) channels which carry melt water through the glacier to the toe begin to freeze and contract. The effect of the hydrologic network closing at the end of the melt season is an aspect of glacial hydrology and chemistry that is currently insufficiently addressed. The timing of water delivery from glaciers is uncertain as climate change will fundamentally alter glacial recession rates and melting. For example, glacier recession in western Canada has led to changes in melt water pulses in the late summer with negative consequences for populated downstream environments, such as the arid Canadian Prairies, that are now subject to an impending water crisis. In particular, the Athabasca Glacier retreated only about 200 m between 1844 and 1906 but receded over 1 km during the next 75 years and lost nearly half its volume.

Here I am, arrived in Antarctica. Even if it's the 6th time for me on the White Continent, it's still an extraordinary feeling to be here, like disconnected from the "normal" world.

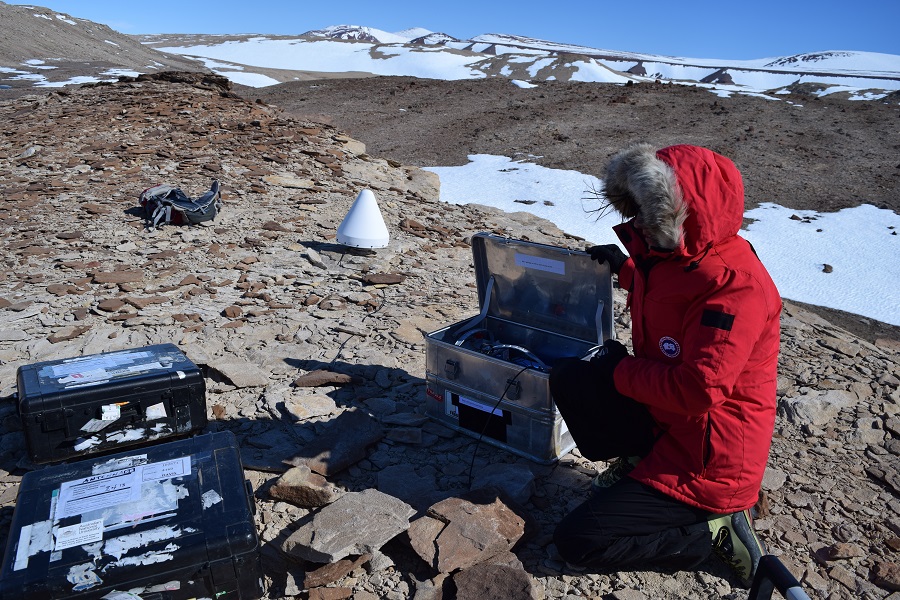

Here I am, arrived in Antarctica. Even if it's the 6th time for me on the White Continent, it's still an extraordinary feeling to be here, like disconnected from the "normal" world. For that part of our work, we installed a series of GPS beacons around the Amery ice shelf: a first one close to Sanson Island (called Landing Bluff), a second one on Beaver Lake (on the Western part of the Amery) and a last one on the South of the ice shelf. These three locations have been chosen to continue the uplift records started about 7 years ago. These post-glacial rebounds signals are supposed to be around 1 to 2 mm/year in that region and are consequences of the melting of a previous Ice-Sheet during the last deglaciation (about 20 000 years ago). We can then expect to record uplift signals of about a centimetre over that period.

For that part of our work, we installed a series of GPS beacons around the Amery ice shelf: a first one close to Sanson Island (called Landing Bluff), a second one on Beaver Lake (on the Western part of the Amery) and a last one on the South of the ice shelf. These three locations have been chosen to continue the uplift records started about 7 years ago. These post-glacial rebounds signals are supposed to be around 1 to 2 mm/year in that region and are consequences of the melting of a previous Ice-Sheet during the last deglaciation (about 20 000 years ago). We can then expect to record uplift signals of about a centimetre over that period. The GPS beacons used are not autonomous stations, and are then not supposed to be recording for more than 10 days (approximately the autonomy of our batteries). This aspect complicates a lot our work, because it implies picking up the equipment 10 days later. So making two trips at the same place, and hence finding two weather windows to fly there. The flights are pretty long (from 1h30 for Landing Bluff up to 5 hours for Dalton's Corner) and imply the use of the helicopters and the Twin-Otter.

The GPS beacons used are not autonomous stations, and are then not supposed to be recording for more than 10 days (approximately the autonomy of our batteries). This aspect complicates a lot our work, because it implies picking up the equipment 10 days later. So making two trips at the same place, and hence finding two weather windows to fly there. The flights are pretty long (from 1h30 for Landing Bluff up to 5 hours for Dalton's Corner) and imply the use of the helicopters and the Twin-Otter. For the first part of our install, we have set up the first GPS on Landing Bluff on top of a Russian station, plugging it into the GPS antenna which remained there during the past 7 years completely intact. The conditions are great: a lovely sunshine make us forget that we are in Antarctica...

For the first part of our install, we have set up the first GPS on Landing Bluff on top of a Russian station, plugging it into the GPS antenna which remained there during the past 7 years completely intact. The conditions are great: a lovely sunshine make us forget that we are in Antarctica... After three hours of flying, a first peak appears in front of us: The Prince Charles Mountains. We put us deeper into a gorge and after few minutes we spot our GPS antenna.

After three hours of flying, a first peak appears in front of us: The Prince Charles Mountains. We put us deeper into a gorge and after few minutes we spot our GPS antenna. Byers Peninsula constitutes the largest ice-free area in the South Shetland Islands. It is a protected area in Livingston Island, with the largest biodiversity in Antarctica. Research activities are regulated by the Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 126 (Byers Peninsula, Livingston). Byers Peninsula has a relatively flat relief with more than 110 lakes/ponds, some of which have been studied within the HOLOANTAR project (

Byers Peninsula constitutes the largest ice-free area in the South Shetland Islands. It is a protected area in Livingston Island, with the largest biodiversity in Antarctica. Research activities are regulated by the Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 126 (Byers Peninsula, Livingston). Byers Peninsula has a relatively flat relief with more than 110 lakes/ponds, some of which have been studied within the HOLOANTAR project (

For the next couple of weeks I am joining the Juneau Icefield Research Program (JIRP) , which provides an unrivaled educational and expeditionary experience in the Coast Mountains of Alaska and British Columbia and give students a wide range of training in Earth sciences, wilderness survival, and mountaineering skills. Students learn from leading scientists in a wide range of disciplines, including glaciology, geology, climatology, and biology.

For the next couple of weeks I am joining the Juneau Icefield Research Program (JIRP) , which provides an unrivaled educational and expeditionary experience in the Coast Mountains of Alaska and British Columbia and give students a wide range of training in Earth sciences, wilderness survival, and mountaineering skills. Students learn from leading scientists in a wide range of disciplines, including glaciology, geology, climatology, and biology. The classroom is the Juneau Icefield, situated in the Coast Mountains of the Tongass National Forest and Atlin Provincial Park. During the trip students, staff and faculty traverse this terrain, conduct research, participate in a curriculum of lectures and research projects, and live in this amazing landscape – thus the need for durable, weatherproof and warm gear from Canada Goose! And I feel privileged to be able to contribute this year to what has been described as "... the best – and grandest – Earth Sciences classroom in the world." — Dr. Benjamin Santer, JIRP Faculty; Investigator of Climate Change, Lawrence Livermore National Labs; Member U.S. National Academy of Sciences. The ability to stimulate cross-disciplinary collaboration among students from the United States and around the world with scientists engaged in all aspects of Earth systems science greatly benefits glaciological research in the long run as it encourages interdisciplinary research and interpretation, a goal that's a priority with the Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS), and one I'm proud to be associated with.

The classroom is the Juneau Icefield, situated in the Coast Mountains of the Tongass National Forest and Atlin Provincial Park. During the trip students, staff and faculty traverse this terrain, conduct research, participate in a curriculum of lectures and research projects, and live in this amazing landscape – thus the need for durable, weatherproof and warm gear from Canada Goose! And I feel privileged to be able to contribute this year to what has been described as "... the best – and grandest – Earth Sciences classroom in the world." — Dr. Benjamin Santer, JIRP Faculty; Investigator of Climate Change, Lawrence Livermore National Labs; Member U.S. National Academy of Sciences. The ability to stimulate cross-disciplinary collaboration among students from the United States and around the world with scientists engaged in all aspects of Earth systems science greatly benefits glaciological research in the long run as it encourages interdisciplinary research and interpretation, a goal that's a priority with the Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS), and one I'm proud to be associated with.